Meta won the war for infinite attention and immediately lost the peace.

They got exactly what they wanted: 93% of Instagram usage is watching videos from strangers. Facebook is 83% algorithmic feed. Pure, uncut engagement.

Turns out, infinite video from people you don't know has a name we already invented in 1950: Television.

For twenty years, tech companies optimized every platform toward the same end state. Student directories became feeds. Messaging apps became feeds. AI art tools became feeds. Podcasts moved to video. Newsletters added video.

Everything flowed toward the same product: endless short videos recommended by machines.

Raymond Williams called this “flow” in 1974. He wrote that television shifted culture from discrete items (books, plays, albums) to continuous streams where nothing is essential and everything is incidental.

TikTok and Instagram are even purer than television. On TV, you might tune in for a specific show. On TikTok, nothing is specific. The algorithm itself is the product.

The companies finally built a perfect flow.

Enter Gen Z.

They're the first generation with a full dataset. They grew up on Instagram when it was photos of friends. They watched it transform into algorithmic Reels from strangers. They saw Snapchat become Stories, Stories become Reels, Reels become indistinguishable from TikTok.

They watched every platform become the same platform.

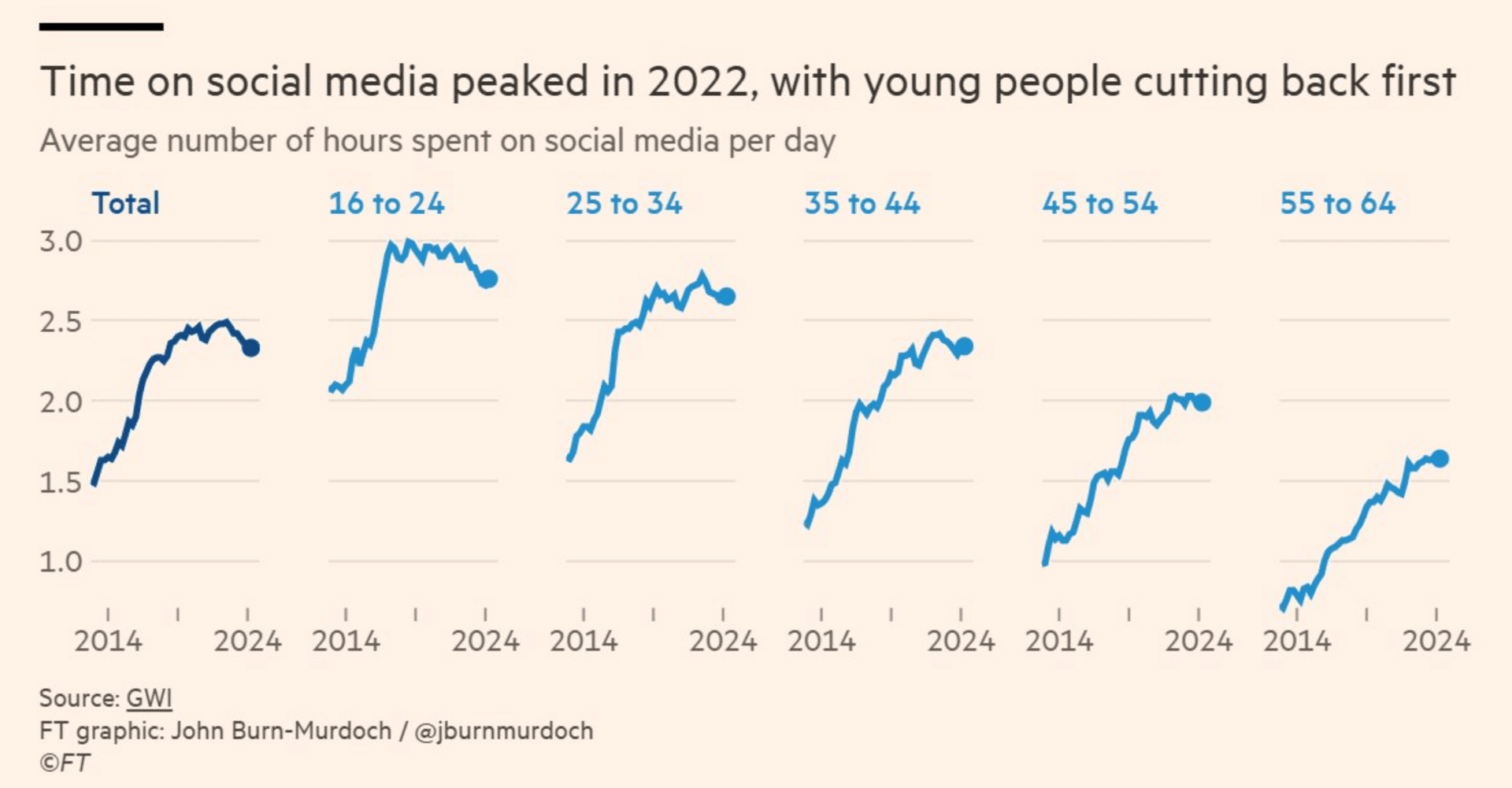

It has gone largely unnoticed that time spent on social media peaked in 2022 and has since gone into steady decline

Derek Thompson tracked what happened in the 1990s when Americans got six extra hours of leisure per week. They could have learned skills, built a community, and had more kids. Instead, they poured all of it into watching TV.

Television didn't just change what people watched. It changed who people knew.

Husbands and wives spent four times more hours watching TV together than talking. People stopped volunteering, hosting dinners, and going to church.

We thought the internet would reverse this. We built super-television instead.

Smaller screens, smarter algorithms, infinite content. Same isolation, faster delivery.

Here's what nobody expected: the generation that grew up fully immersed would be the first to walk away.

Gen Z has enough data to see the pattern. Their parents watched them get optimized into anxiety. They felt the difference between scrolling for three hours and doing literally anything else. They developed immunity to the thing that was supposed to be irresistible.

Infinite stopped being the feature. It became the poison.

Companies spent $500B building infrastructure for endless video, and the humans started wanting bounded experiences again. Things that end. Things that happen once. Things that require showing up.

The entire economic model assumed “more” would always mean better.

You can finish the weekly publications. Podcasts with final episodes. Events at specific times in specific rooms. Communities that close applications. Products that limit usage.

Finite is the new premium.

Meta's legal filing admitted what users already felt:

Today, only a fraction of time spent on Meta’s services—7% on Instagram, 17% on Facebook—involves consuming content from online “friends” (“friend sharing”). A majority of time spent on both apps is watching videos, increasingly short-form videos that are “unconnected”—i.e., not from a friend or followed account—and recommended by AI-powered algorithms Meta developed as a direct competitive response to TikTok’s rise, which stalled Meta’s growth.

These aren't social networks anymore. They're television networks with comment sections.

The companies optimized so hard toward engagement that they went beyond what people actually wanted.